It’s late summer, and crowded into a double horseshoe of gold-clothed tables are dozens of delegates representing 16 groups responsible for civil war that has lasted nearly 70 years.

On one side sits the Union Peacemaking Work Committee (UPWC), a negotiation team representing the government, a quasi-civilian democracy with a quarter of parliamentary seats and key ministerial posts reserved for the military. On the other, the Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) represents 15 officially recognized armed ethnic groups and a number of unofficial groups, each comprised of a distinct tribe. The Kachin. The Karen. The Rohingya. The Shan. The Kokang. The rest.

This is not a scene from the latest action blockbuster. This is the situation in Myanmar (also known as Burma) in the summer of 2015.

Among those at the peace table is Cairn alumna Ja Nan Lahtaw ’93/G’95, facilitator and advisor to the armed ethnic groups.

In reportedly the first meetings in decades between the government and collective representation of armed ethnic minorities, Ja Nan and other negotiators helped lead the groups to the preliminary signing of a nationwide ceasefire draft on March 31st. After nearly two years of negotiation, a final version of the agreement was signed on October 15th — including, however, only eight of the 15 armed ethnic groups considered eligible by the government.

Without the government’s inclusion of several groups involved in recent clashes with the state army, the nation’s largest armed groups are among those refusing to sign. Yet, while not truly “nationwide,” the agreement is viewed by signing groups as the beginning of a “bloodless battle” for justice — potentially opening the door for representatives of those ethnic minority groups, now removed from the government’s list of illegal organizations, to participate in the mainstream political process.

Despite the continuation of military conflict throughout the nation, the representatives of the armed ethnic leaders have found in the process hope for peace. For Ja Nan, the participation of women and minorities in the mainstream political process is itself a victory for peacebuilding.

“Creating a space for national dialogue, a space that includes women and civil society, is essential for us to move forward in our country,” she says.

Although excluded from Myanmar’s formal peace processes until two years ago, women like Ja Nan have long been at the forefront of diverse grassroots peacebuilding and mediation efforts in Asia.

“The international perception of peace is often limited to politics, to negotiations at the peace table,” Ja Nan says, “but the peace building concept is very broad. The work that people do on the ground is also part of peace.”

“The biblical meaning of shalom includes people’s rights to have their basic physical and psychological needs met. Jesus cared for these needs. Our belief is set on the Prince of Peace, who provided for the needs of the people, even on the Sabbath day.”

One of these grassroots efforts is the Nyein (Shalom) Foundation, an NGO devoted to promoting peace and development among peoples from all of Burma’s ethnic and religious groups. Involved from the beginning of this organization founded by her father in 2000, Ja Nan stepped into the directorship in February 2014.

“Even though we are not church-based, we base our values on the biblical meaning of shalom: ‘how things should be.’ If things are not as they should be, it is not peace. When you’re working with starving people, with sexually abused women, you are building peace. Shalom includes people’s right to have their basic physical and psychological needs met: food, shelter, clothing. You should be able to feel love, to have dignity, to tell the truth.

“If you look at the Gospels, Jesus cared for these needs. Our belief is set on the Prince of Peace, who provided for the needs of the people, even on the Sabbath day.”

As an international student at Cairn from 1989–93, Ja Nan always knew that she would return to Myanmar. “I never even explored what the legal process would be to stay in the US,” she says. “Knowing that there are so many in the US with the capacity for ministry, I felt like it would be a waste for me to stay in the States.”

A dual-degree Bible and Music Performance major in undergrad, Ja Nan had her heart set on serving the church through music: “In those days, my engagement was very confined to the church community. When we were youths, my parents had encouraged us to sing in the choir, and I had volunteered as a church pianist. I thought, ‘This is how I can serve God. This is how I can help people.’”

During her time at Cairn, “I realized that interest in music and talent in music are two different things.” With a laugh, she shares, “I discovered that I did not want to play piano. I have short fingers!”

Short fingers did not stop Ja Nan from using her music education powerfully to serve the church. For five years after returning to Myanmar, Ja Nan taught music classes and helped to transform the local church’s capacity for music ministry. In addition to developing an updated music theory book (still used throughout the nation’s Baptist churches), she redeveloped the curriculum at Kachin Theological College to emulate Cairn’s music program. One of her proudest accomplishments was the formation of a touring chorale group like the one she had so enjoyed during her time at Cairn.

But God had different long-term plans for Ja Nan’s ministry — plans that He began preparing her for while still a student at Cairn.

“At Cairn, the counseling that I learned was about redeeming relationships — both vertical (between people and God) and horizontal (between God and people).

That relationship building is an essential part of peacebuilding. It is an essential part of the biblical meaning of shalom.”

“While I was studying here, I had regular contact with the college back home,” she says. “They wanted to know, ‘How many pianos should we buy, so that you can teach lessons when you return?’” Anticipating a teaching position in higher education, Ja Nan decided to pursue a master’s degree before leaving Cairn. She chose Christian counseling as her field, she says, because it was about helping people. Little did she imagine how far beyond the walls of her church God would use those skills.

“At Cairn, the counseling that I learned was not psychoanalysis; it was about redeeming relationships — both vertical (between people and God) and horizontal (between people). That relationship building is an essential part of peacebuilding. It is an essential part of the biblical meaning of shalom. That background is what helps me most with what I do now.

“Also in the counseling program, we had to understand, ‘What are the deeper issues when someone is talking?’ We need to explore by asking further, deeper questions. Those listening and questioning skills that I developed in the counseling program have been very helpful in my facilitation of peace talks, because it’s your job to understand what the person is trying to say and help them clarify.”

Today, Ja Nan’s own participation as advisor and facilitator in formal peace processes is a testimony to the hard-won victories of decades of peace work. A minority on every front — as a woman mediator, a Christian in a predominantly Buddhist nation, and a member of the Kachin tribe — Ja Nan’s pursuit of peace has taken her far beyond the borders of Myanmar. Most recently, this October she spoke before the US State Department before traveling to the UN in NYC to receive the international N-Peace Award honoring her work.

But for Ja Nan, the real reward is the change that God is working in the lives of her people. “Since I was small, there was a story that I heard from the community about their struggles. Their story was always fresh in my heart. Because of Myanmar’s situation, the Kachin churches are deeply invested in the ties between these social needs and the gospel. The church is a space not just for the spiritual, but for the poor, the powerless, and for those who don’t know where else to go. I now work outside the walls of the church, but this peacebuilding work is my ministry.”

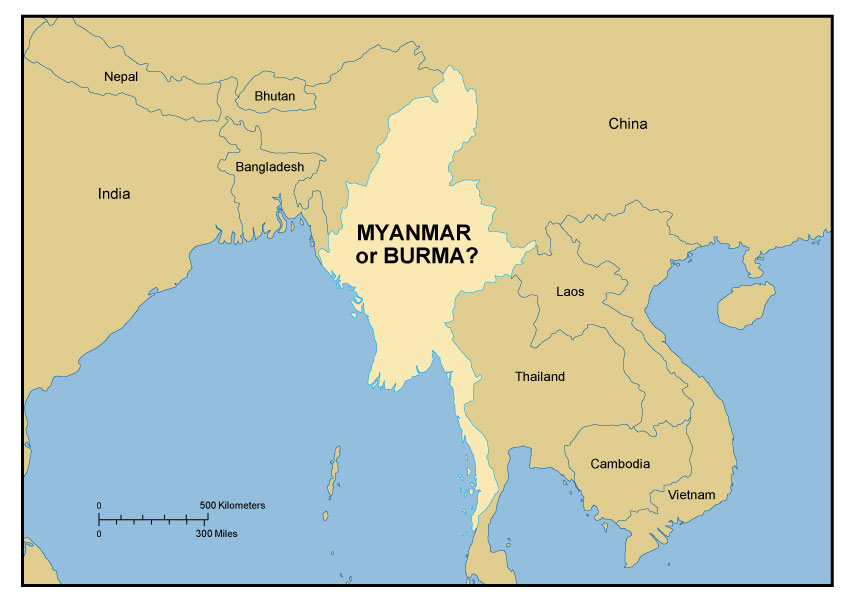

BURMA OR MYANMAR? NOT AN EASY QUESTION

In the media, the names “Burma” and “Myanmar” seem to be used interchangeably for the same nation. Cairn librarian Nang Tsin Lahtaw G’98 offers this explanation for the inconsistency:

“When the unelected military regime changed the English name in 1989, this name change occurred without the consent of the Burmese people. Even though many of the people are not ethnic Burmans, they do not accept the government’s change to ‘Myanmar.’ It is still Burma to them.”

Today, journalists, governments, and international organizations continue to disagree on how to refer to the country. Many see adopting “Myanmar” as an affirmation of the current government, which has been held responsible for gross human rights violations including violence against ethnic and religious minorities, political repression and censorship, human trafficking, torture of prisoners, and recruitment of child soldiers.

Many nations, including the US, have also persisted in using the term “Burma” in protest of the military leadership’s refusal to yield power after losing the country’s 1990 elections. The ruling military junta placed the elected democratic leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, under house arrest for nearly 20 years. Although democratic reforms in 2011 have changed international relations, the government still has a long way to go — further muddling the issue of what to call Burma/Myanmar for visiting leaders like President Obama.

“I’LL MAKE A WOMAN OUT OF YOU”: MAE STEWART AND JA NAN LAHTAW

Mae Stewart ’52 clearly remembers the day she met Ja Nan: “I was standing by the elevator on the second floor when I saw a young woman standing there, looking lost. Fran Emmons explained to me that Ja Nan had just arrived in the US four weeks late for the semester, delayed in Burma by some trouble with visas or whatnot.”

Like scores of international students throughout the years, Ja Nan found in Miss Stewart a friend and mentor — and housemate. Mae remembers, “Summer came and she had nowhere to stay, so she said, ‘Can I come stay with you?’ I said yes, and the rest is history.”

And history was made — not least Ja Nan’s involvement this year in drafting a nationwide ceasefire agreement, an achievement that she believes would not have happened if not for Mae’s mentorship. Ja Nan remembers, “When I first came, I wasn’t like this. I was very shy. Normally, I spoke very few words, a couple words.”

But Mae would soon change all that. “At Miss Stewart’s house, we had a Japanese girl, a Korean girl, a very quiet American girl, and myself. The house rule was that we always eat dinner together. Miss Stewart would ask, ‘Ja Nan, how was your day?’ And everybody would say, ‘Fine.’ Knowing how dynamic Miss Stewart is, she got sick of hearing just one reply. So she started saying, ‘Okay. I want to hear more.’

“I learned a lot from her. Learning to share. Learning to be decisive. I have become a multitasker like her. My cousins say, ‘You’ve become just like Miss Stewart.’

“She always used to say, ‘Ja Nan, I’m going to make a woman out of you.’ After all this, I joke with her: ‘Miss Stewart, you have made a woman out of me now.’”

THE LEGACY OF BURMESE INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS AT CAIRN

“Since Ja Nan, we have had 33 students from Burma at Cairn… and I know every one of them.”

— Mae Stewart

Ja Nan is far from the only international student from Burma to graduate from Cairn. In the 12 years since Ja Nan received her bachelors’s degree in 1993, Cairn has graduated 33 international students from Burma. With few exceptions, these alumni are family or friends of the Lahtaws. They serve Christ both in Asia and across the United States.

But with whom did this legacy begin?

The story begins in 1945, when Dr. Donald Kreider graduated from Cairn and obeyed God’s call to serve as a missionary in northern Burma. He and his wife served with the American Baptist Mission among the Kachin people until 1965, possibly the very last missionaries to leave the country after the military junta took over four years earlier. Years later, during a brief visit to the community where he grew up, Dr. Kreider’s son Ron met Ja Nan, whose seminary studies had been cut short by an uprising in the nation’s capital in 1988.

Upon discovering that Ja Nan wanted to pursue music ministry, Ron encouraged her to study piano at his father’s alma mater. Motivated by a heart for students seeking education abroad in order to return and serve in their home countries, Ron and his family sponsored Ja Nan’s I-20 and visa, essential documents for international study. They became, Ja Nan says, her “American family.”

Following in Ja Nan’s footsteps, eleven Lahtaws have since graduated from Cairn, including her brother Zau Ma ’01, her sister Roi Maw ’96/G’00, and many cousins. Some have returned to Burma, including Zau Ma, who works alongside Ja Nan at the Shalom Foundation. Others have pursued careers in the United States, many serving immigrants from their home country by pastoring Burmese congregations or providing interpretation services.

Of the 22 other Burmese alumni, most are the Lahtaws’ family friends or friends-of-friends. Some have also returned to serve in Burma, such as Roi Nan Sabaw ’08/G’11, now teaching at Kachin Theological College, and Stanley Hmung ’98, who works in music production.

Just as Mae Stewart’s hospitality serves as an example of the difference one spirit-led relationship can make, the legacy of the Kreider family demonstrates the widespread Kingdom impact that can stem from a single act of encouragement from an alumnus or friend of the University.

DO YOU KNOW A STUDENT WHO BELONGS AT CAIRN?

Let our Admissions team know!

By connecting us with a prospective student who would thrive in at an academic institution centered on Christ and His Word, God can use you to begin a new legacy at Cairn.

Visit cairn.edu/referastudent