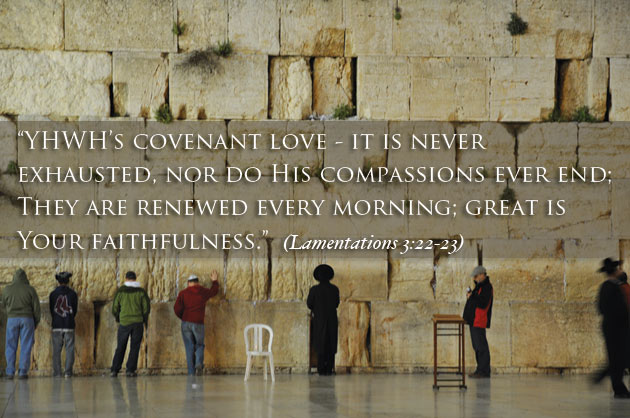

[dropcap3]“G[/dropcap3]reat Is Thy Faithfulness.” That wonderful hymn of the faith was a regular part of worship in the churches of my childhood and my youth. The song tells of YHWH God’s loyalty to His people throughout all seasons of life and throughout all generations.

While we as the church love and cherish these two lines of Scripture, we are sometimes at a loss when we read this stanza in its literary context. Lamentations is a book about the most tragic and terrible moment in Israel’s history. It tells of parents eating their children, virgins being raped, youths and elders slaughtered in the streets. Why is such a book part of the canon of scripture? Why are these two verses in it the lone hopeful strain in the entire book?

In his article, “The Costly Loss of Lament,” Walter Brueggemann* exposes the deficiencies that result in the life of the church when laments are marginalized in liturgy and interpretation.1 He argues that laments provide a sense of genuine covenantal interaction between God and human beings: “Where lament is absent, covenant comes into being only as a celebration of joy and well-being….The greater party (God) is surrounded by subjects who are always ‘yes-men and -women’ from whom ‘never is heard a discouraging word.’”2 He wonders: what kind of relationship would we have with God if we could never bring to Him our complaints, our anger, and our pain?

In a Western culture increasingly apathetic or even hostile to Christianity and the God of Scripture, the problem of evil is once again an apologetic concern. The New Atheists—Dawkins, Hitchins, and others—point to wars, plagues and natural disasters in arguing that the almighty God of Scripture cannot exist; either He is incapable of intervening to stop wars, earthquakes and hurricanes (and is therefore not omnipotent), or He is unwilling to do so and is therefore unworthy of reverence and worship.3

The problem of evil is real, and it troubles Christians and non-Christians alike. Evil exists in our world and within each of us. Lamentations is a book of Scripture that confronts the evil within and without. Careful consideration of Lamentations can give us pastoral and apologetic tools to speak powerfully to suffering people in a broken world.

Fragmentation

The destruction of the Jerusalem temple in 587 BCE transformed the worship of YHWH. The Babylonians deported the elites of Judah—mostly urban types from Jerusalem (2 Kgs 25:8-11). The priestly class, the royal family, the scribes, the wealthy landowners—these were part of only a few thousand who were taken to Babylon: between ten and twenty percent of Judah’s population. Most of the poorest Judahites stayed and worked the land for new Babylonian masters (2 Kgs 25:12). Some elites fled to Egypt and smaller countries surrounding Judah (Jer 42-46).

The Jews after 587 BCE were separated not only from each other, but also from the destroyed Jerusalem temple. At this watershed moment the religious and cultural identity of the people was forced to change: they had to discover new ways to conceive of YHWH’s presence with them. Scripture and prayer, rather than worship in a special location, became more important. Synagogues could be built anywhere there were ten Jewish men—not just on a particular mountain in Palestine. The events of 587 BCE drove the people of Israel out into the world and forced them to rely on YHWH in different ways than they had previously.

Religious expressions that could tell of God’s omnipresence and His universal sovereignty (the notion that He is not a local god of one nation only) became increasingly important to Jews during this period. For example, Ezekiel’s great vision of YHWH God coming on a chariot of four beasts, with four wheels of fire that could go in any direction, would speak to the community of exiles in Babylon: YHWH is with you far away from your homeland—He comes to judge, but He also comes to save.

The regathering of scattered Israel seems to be of utmost importance in the literature from this period. If YHWH could ever forgive His people, as He promised He would, that forgiveness would lead to a reconstitution of the society, the religion, the culture, and the people from all the lands in which they were scattered.

The Walls Cave In

When the temple was destroyed, all of God’s promises—to Abraham, to Moses, to David, to Israel—were thrown into doubt. YHWH had abandoned His temple and allowed it to be desecrated by enemies. The king and the elites were taken into exile, never to be heard from again. Many people were killed or starved; some who survived fled to Egypt, or lived in slavery in the smoldering ruins of Judah. Everything they had ever known was destroyed, and everything they had believed was now called into question.

Lamentations is a set of five poems that commemorate and reflect upon the destruction of the temple by the Babylonians. Amidst the descriptions of horrors almost too terrible to speak about and the expression of shock, pain, anger, and despair, these poems ask whether it is possible to make sense of it all.

In the ancient world, laments were socially and religiously sanctioned, controlled ways of expressing grief.4 The performance of a lament fulfilled several important functions in a community. First, laments contributed to social cohesion in the face of catastrophe.5 Through the ritual process, the mourner received comfort from a community, those who mourned alongside him. After some prescribed period, the mourner must accept the loss and “move on” as tolerably as possible without the deceased, once again meeting the daily difficulties of human existence. Some cultures facing collective tragedy actually designated a representative mourner—an individual whose specific job was to lament publicly on behalf of the community.

Second, laments were a way of elevating the voices of survivors before the world and before heaven.6 This motivation of the ritual lament could be characterized as protest. The mourner made prominent in the public sphere the injustice of the tragedy and the transgression of the human or divine perpetrator. The sentiment is: things are not as they should be, and it is the responsibility of the deity/royalty/community to change the status quo until justice is restored.7

A third purpose of laments in ancient cultures was to provide some sense of completion of the tragic event—a way for individuals and communities to move forward after tragedy.8 The lament informed the gods and the human community that the tragedy had been accepted as a warning. For example, laments were used at the dedication of a rebuilt temple in order to put the past to rest and ask the gods to bless the future.9 Laments also reflected upon the transgressions that led to the tragedy, and instructed the audience how to avoid the tragedy that befell the deceased.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.