Throughout its history, Cairn University has generally been a place to prepare for a degree in ministry—particularly in the pastorate. Gradually, the societal reach of the University expanded beyond the pastor role alone, additionally venturing into the fields of social work, business, and eventually, the various liberal arts and sciences degrees offered today. This expansion of what it means to receive a Cairn education has had the effect of producing students who maintain a distinctly Christian approach to jobs and expertise that one could consider “secular.”

Between these positions of ministry-proper and Christians in “secular” jobs stands the role of chaplain. It’s a term with many meanings, depending on whom you ask. Chaplains can serve in nearly any context you can think of, and they can hold many different personal beliefs, be they Catholic, Muslim, Buddhist, Jewish, or even atheist/agnostic and humanistic.

So what does it mean to be a chaplain, especially for someone seeking to live in a distinctly Christian way? If it can mean so many different things, can the word—and more importantly, the role—mean anything?

What is “Spiritual Care?”

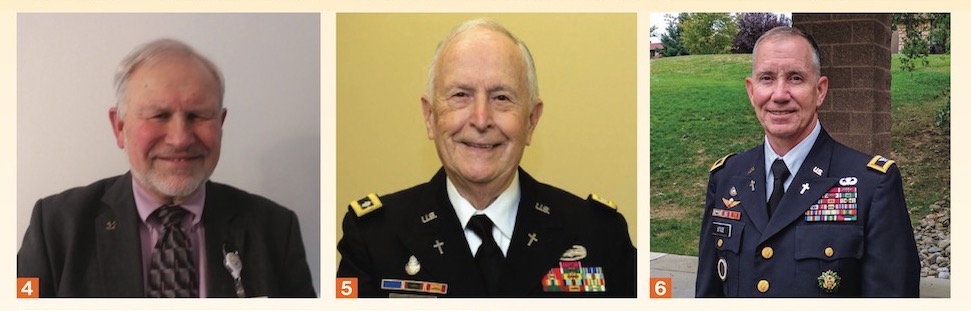

Dean McFadden ’75 serves as a chaplain at Genesis Health System in Illinois. He found his way into chaplaincy after the church he pastored encouraged him to pursue some further education. He took part in a clinical pastoral education program that included 300 clinical hours in a cardiac unit that ultimately changed his whole career: “After one week of clinicals, I was experiencing adrenaline highs! I thought to myself, ‘I’d love to figure out a way to do this and get paid for it.’” A year later, Dean took a full-time position with Genesis.

The chaplaincy role at Genesis is part of their approach to care for patients holistically. Alongside the efforts of nurses, physicians, social workers, and therapists, Dean and the other chaplains on staff provide spiritual care. Dean either offers this care himself, or, if patients have a pastor or practice another faith, he coordinates with their place of worship. Over the years, he has provided rosaries for Catholic patients and advocated for those who object to certain medical procedures on the basis of beliefs. He’s a spiritual support, exploring what clients believe and how it can help them handle the stresses of being hospitalized.

Still, “spiritual support” can take on many forms. Most of the patients Dean interacts with would be classified as the “nones”—people who do not belong to a specific religion or denomination, but many of whom are not fully shut off from spirituality. So what does a Christian chaplain do? If the patient is willing, he represents Christ by sharing the gospel with them. Other times, it looks like just being there.

This shows up most noticeably in one of Dean’s unlikely favorite parts of the job: accompanying the dying. As families gather around loved ones nearing the end, Dean simply sits with them as a present observer. Sometimes the family might offer stories and memories; other times they sit silently for hours. When a nurse makes the final announcement of the patient’s passing, Dean is there for the cries of sadness or yells of anger. “That’s okay,” he explained. “That’s what initial grief looks like.” Later, as emotions settle, families will turn to Dean and thank him for all he did. “I mostly just sat there with them,” Dean said. “It’s called pastoral presence.”

Responding to Heart Cries

In settings where direct proselytizing is discouraged or forbidden, chaplains get a unique opportunity to embody the Immanuel (“God with us”) through pastoral presence: a vital task that is rarely rejected. Jack Crans ’72 attempts to display Christlike presence in his role as chaplain for several organizations in Coatesville, PA, and beyond, including chaplain-on-call for Chester County Prison.

Over several decades, Jack has worked to earn the trust and respect of his community. He’s solidified that trust throughout the levels of the prison system, serving the prisoners along with the guards, the wardens, the police, and the social workers. His colleagues see the presence he and his ministry have: “When kids come to our jail at the age of 16, they look at me and the first thing they say is, ‘Mr. Jack.’ We’ve known them since they were little kids. The staff sees that and knows that. It makes a difference.”

Jack, like Dean, navigates the intricate responsibilities of the chaplaincy, including allocating religious resources for inmates of various faiths and advocating for their practices. On one occasion, Jack advocated for his colleague, a Muslim chaplain, to receive funding that would supply Qurans to inmates who request them. He had enough Bibles, and his colleague lacked enough Qurans; Jack petitioned the board to transfer the Bible funds in his budget to his Muslim counterpart as an act of generosity.

It is this very professionalism that has built mutual respect between Jack and the Muslim chaplain and with the secular system in which they both work. The correct course of action is not always clear-cut, but through his consistent presence and example, Jack has earned the right to speak boldly about the gospel and God’s heart for the suffering. “I try to biblically respond to the heart cries, the tangible urgencies that are reflected in the criminal justice system,” he explained. “They’ve never turned away from our message for one reason: we don’t just preach.”

Freedom in Pluralistic Environments

Perhaps the most commonly thought- of chaplaincy role is that of military chaplain. Cairn alumni like Sang Pak ’99/G’07 have been involved in this important work across decades.

In addition to pastoral ministry and working as a licensed marriage and family therapist, George Vogel garnered extensive experience as a military and hospital chaplain. In the Vietnam era, he served five years of active duty chaplaincy in Korea, Fort Ord, West Germany, and Free Berlin. Then, in 1987, he became a hospital chaplain for the Department of Veteran Affairs in Long Beach, CA.

Sang is an ordained Presbyterian minister and an Army chaplain. He serves under a military commander, as all army chaplains do, and as he explained, “Army chaplains exist to ensure the free exercise of religion in the context of military service as guaranteed by the Constitution.” This role includes leading services and worship, funerals, weddings, counseling, and anything else he might do as a “regular” minister.

During his military experience, which included the invasion of Iraq in 2003, Sang saw how the chaplains he interacted with played an important role in the effort. When his military contract ended, he returned to Cairn to obtain an MDiv, thinking he would enter the pastorate, but he quickly found that a traditional local church ministry role wasn’t for him. Still serving in the Army reserve, he was notified one day to report for a muster call. This routine call later led to a bigger call to pursue a career in chaplaincy.

Like his fellow Christian chaplains, Sang provides pastoral presence to those he serves in the military. Though many he interacts with wouldn’t identify as Christian—and a few might even be called “anti-religious”—he also has those who are spiritually hungry: “As Jesus said, the harvest is plentiful!” Sang has the freedom to and has experienced the joy of sharing the gospel with military members.

He talks about his work environment as “pluralistic”: an atmosphere where members of society from varying backgrounds and beliefs must work together. In such an environment, he’s not as restricted as some of us on the outside might think; while there are rules and regulations that govern what a chaplain can and can’t do, “there is also great freedom and great opportunity.” Maintaining professionalism still allows for genuine interaction with others, even on a spiritual level. As a Christian and an experienced military member, professionalism in reference to faith comes naturally for Sang. “I don’t find it that hard, and it shouldn’t be,” he explained. “We should treat all people with dignity and respect, regardless of different views. Presenting the gospel requires love and patience— never force.”

The Dangers of the Job

It’s not an easy job, and it’s not without its workplace hazards. Working among all forms of human suffering like loss, isolation, violence, and tragedy can take a toll. Moments of pastoral presence with a grieving family, as Dean described, can be difficult to bear. Jack hears the continuing heart cries of the criminal justice system, cries that ring at a frequency that can wear on the ears and tire the spirit. Sang, too, fights potential burnout from overworking and the heavy reality of loss, especially among young military men and women who leave behind friends, loved ones, and families. This work—similar to that of social workers, nurses, therapists, pastors, and others in the helping field—includes great discouragement and sadness.

Sang Park is also an ordained Presbyterian minister in his work as an Army chaplain.

Sang calls these the dangers of identity and complacency. In response to the bureaucratic and professional demands, he’s seen chaplains work themselves into a type of administrative role, unthinkingly trading their pastoral identity as shepherd of a flock in return for status, privilege, and rank. Others become tired or bored of the pain they see around them and fall into complacency. Paperwork and a lukewarm spirit may bury a passion for disciple-making that was once there. The perils familiar to the pastorate afflict chaplains as well.

The challenges, however, speak not only to the harsh realities chaplains face, but also to the unique and profound opportunity they receive to bless others in Christlike service. Chaplains accompany those they serve in the richest of their human experiences, be they experiences of joy and excitement or grief and pain. Sang speaks both of the joys of world travel and beachfront weddings and the sorrows of loss among young soldiers. Dean gets to see patients heal and leave the hospital fully recovered; he also sits in tears and sorrow with grieving parents who have lost a child.

Life hands out measures of both joy and pain, and both offer their own meaning. Chaplains, like pastors and therapists and social workers and good friends, accompany us in these meaningful experiences, yet they specifically carry the unique role and responsibility of being structured within institutions. The governmental and institutional expectation for chaplains to be included in organizations across the world provides an “in,” a societally sanctioned foothold, for chaplains to embody Christ’s hands and feet to the world and share the good news of the gospel. In these ways and more, the position of chaplain means a lot.

Juston Wolgemuth ’19 is the communications specialist at Cairn. He can be reached at jwolgemuth@cairn.edu